Discography >>

ALBUM

PURCHASE

RELEASE DATE

DURTATION

GENRE

STYLES

June 27, 2000

46:35

Pop/Rock

Garage Rock

Psychedelic

Garage Punk

TRACK LIST

01. Everything Is Everything

02. Two Much

03. Advise and Consent

04. This Should Make You Happy

05. Black Snow

06. Chances

07. Mother Nature, Father Earth

08. Talk Me Down

09. Dark White

10. Push Don't Pull

11. Smoke & Water

12. King Mixer

13. Unca Tinka Ty

14. Citizen Fear

15. Worry

16. Worry

17. Tell Me What Ya Got

18. Point of No Return

19. 902

COMPOSER

Sean Bonniwell/Harry Garfield

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwelll/Paul Buff

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell/Harry Garfield

Sean Bonniwell

Sean Bonniwell

TIME

1:52

2:02

2:58

1:53

2:30

3:07

2:14

1:48

4:13

2:15

3:19

2:43

2:04

2:28

2:11

2:15

2:06

2:40

1:57

"Even if you promise me my poet will not die...I fear the poet's soul in me has told a poet's lie..."

- Sean Bonniwell

PRODUECED BY>> Sundazed

ENGINEER>> Paul Buff Composer, Engineer

DESCRIPTION>>

- Steve Besch: Photo Courtesy

- Sean Bonniwell: Composer, Guitar (Rhythm), Horn, Liner Notes, Photo Courtesy, Producer, Vocals

- Jud Cost: Photo Courtesy

- Ron Edgar: Drums

- Harry Garfield: Composer, Organ

- Jerry Harris: Drums

- Bob Irwin: Mastering

- Eddie Jones: Bass

- Mark Landon: Guitar

- Tim Livingston: Project Manager

- The Music Machine: Primary Artist

- Keith Olsen: Bass, Vocals

- Clay Pasternack: Photo Courtesy

- Doug Rhodes: Bass, Flute, Horn, Organ, Tambourine, Vocals

- Rich Russell: Design

- Fred Thomas: Musician

REVIEW>> by Richie Unterberger

As this has a mixture of rare singles and unreleased tracks from 1965-1969, it's primarily for converted Music Machine fans, not for those who want just one album by the group or a place to start investigation. That said, it's a pretty interesting assortment of odds and ends, a few of which are among the band's best efforts. Foremost among them is the explosive (and quite innovative for its time) 1966 number "Point of No Return" with its unusual mixture of folk-rock and pre-acid guitar work, as well as a magnificent anguished, subtly anti-war vocal by singer and songwriter Sean Bonniwell.

The moody, building-from-a-smolder-to-a-roar "Dark White," a 1969 outtake, was already heard on the out-of-print Rhino best-of LP. It's also one of Bonniwell's better creations, as well as one of the best lyrical meditations upon the ambiguous tension of sexual desire that you're likely to hear. "Advise and Consent" is a decent obscure flop single, though not one of the group's greatest. As for the previously unveiled outings, the 1965 demos by the Ragamuffins (the trio of future Music Machine members Bonniwell, drummer Ron Edgar, and bassist Keith Olsen) are especially interesting, catching them in their tentative transition from folk-pop to garage psychedelia. "Citizen Fear," one of the latest tracks (from 1969), has the careering sonics and intriguing sociometaphysical (if that's a word) words typical of Bonniwell's better songs. Much of the rest, though, is simply not up to the caliber of the band's best stuff. Still, it's a worthy complement to the (Turn On) The Music Machine album and Sundazed's previous collection of lesser-known material, Beyond the Garage.

PERSONAL NOTE>> by Sean Bonniwell

TERMS & CONDITIONS | Site by:

Copyright © 2012 Uncle Helmet's Music, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

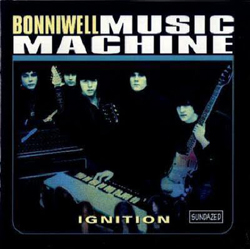

Ignition:

1965. Four songs written specifically for the Music Machine before the group was named. Soon to be known as the Ragamuffins, the trio featured Ron Edgar on drums, Keith Olsen, bass, and writer, Sean Bonniwell, guitar and vocals:

Two Much: The lyrics are chauvinistically delicious, but equal to a car in the race so far behind it eems to be first.

The romantic advice in "Push Don't Pull" is prematurely politically correct as well. As a tactic to persuade full grown women, it's an exercise in futility. It doesn't work on small daughters either. I regard these three songs as born from primal 60's melodies, however, it wouldn't be amiss to assume that "Talk Me Down" points to the future with the same middle finger accused of writing "Talk Talk," and because each song has elements indispensable to its conception they should be regarded as the true birth babies of the Music Machine.

Then there's the thoughtful premonitions in "Chances": Decorated with intonations common to the folk climate of the early 60's, "Chances" approximates the panache of British ballads — ala Gerry & The Pacemakers — but the transferal of that common instrumentation to "militant folk" included a 12 string acoustic lead answered by a punk slam to the brain, an electric lead with sonic distortion that will break your toilet bowl.

All this occurs in "Point of No Return." Featured as "Ignition's" true finale, "Point" is a mixture of folk rock and punk blues, the first of its kind. That the Music Machine invented alternative rock is still open to question. The birth wail of power rock born punk — emanating from the band's garage, is not. Perhaps such a destiny is inevitable for a songwriter who began his career playing trumpet (the photo above appeared on the cover of Down Beat magazine in 1943). For one now known as the grandfather of punk by disciples of the garage, it's not likely that such a misnomer will be validated until he dies from inhaling exhaust.

Slam Shift:

These recordings represent a contemporaneous diversity of late sixties rock.

"Everything is Everything": This is what the fool on the hill said, but a confused guru once said, "I'd give my right arm to be ambidextrous." I was that guru. Advise & Consent stands aside and stares at the enigma of romantic inertia — as derived by an agreement of separation that satisfies no part of its expectations. Not unlike the Clinton administration.

"This Should Make You Happy" refers to producer Brian Ross, and so accommodates commercial clichés of the day it spoofs what never was, bubble gum punk.

"Black Snow" was written an hour after discussing human perceptions of reality with Jose Felliciano, and is meant as a metaphor for what it's like to be blind, physically, and to God.

"Mother Nature/ Father Earth" was recorded a decade before ecology became a term known and used, and its arrangement is due primarily to the talents of then keyboardist, Holly McKinley. God help us if this song becomes an anthem for environmental extremists, we'll all wind up with plastic Christmas trees.

"Dark White" reflects the urgent revisionism of 60's morality: If it moves, fondle it. The blame for this song can be placed squarely on the shoulders of Tarzan, the ape man. This was the only book my father ever read to me. Why he chose the Edgar Rice Burroughs classic is known only to Gloria Steinman, whose next act of feminism will be to have a rib removed. It didn't matter that I couldn't understand how a boy could be raised by apes. I figured if running around in a loin cloth and beating your chest was good enough for Cheetah then it was good enough for Jane. That seemed to be the problem. My father would skip portions of the text referring to any maneuvers leading to seduction. For a long time I believed the Stork delivered Tarzan in diapers, and that he just never got around to taking them off...

Just when you think the Machine's impetuous ignition into pop R&B has run out of gas, "Smoke & Water" shifts gears, and a white man sings the blues without once using the 7th of the chords. At best it can be said of the lyrics that the author was stoned. What makes them worse than they are is that he wasn't.

"Smoke" is a rehearsal song, authored as a means to set sound levels for recording. The lead guitar is a curious mixture; Ravi Shankar practices punk twang. But Mark always played with affectionate wonder — regardless of the genre, which is all the more remarkable when, in "Point of No Return," he was called upon to reveal the source of its deepest agony.

Spontaneous Combustion:

"King Mixer" is a wry evaluation of a roadie dealing drugs. Recorded in New Mexico — on a 4 track — in the dark... "Hey man, all these wires are jammed into one plug! And look at these!! Walter Pigeon wore better headphones. In fact, this microphone looks like the same one he used in the movie Flight Battalion. And why is there a power failure every time I play a G chord? Where are we, in Reno?"

"Unca Tinka Ty": If you're wondering what the title means, think of it this way; the same white guy (who tried to sing R&B) took a stroll through a village in the Congo and then wrote a song.

"Citizen Fear" is a written and performed collaboration with Paul Buff, the genius inventor of ten track recording. It's a peek in the mirror through a glass darkly, with a vocal that almost stands up to the strain of America's assassinated political innocence.

"Worry" is congenial to a fault, and is shamelessly guilty of imitating Beatleesque country pop. But it accommodates an infectious charm that is somehow recast when it becomes the intro for the vocal version. Sung by drummer Ron Edgar, he remarked with sardonic confidence (after completing the vocal in one take), "Ringo Starr, eat your heart out."

The aforementioned "Point of No Return" is next to last, and returns the Machine back to the garage with a tank full of folk/rock punk — discharged by way of anti-war spontaneous combustion.

"Tell me what Ya Got": This song was another first, the first to identify the "me" generation. Unfortunately, it wasn't and won't be the last to do so. If you're skeptical about this, then keep watching television and believing the government.

"902": A touring musician, desperate for contact with his girlfriend, must pacify a suspicious father, a militant operator, and a belligerent pay phone. The laugh you hear from producer Brian Ross needs explaining. Upon appreciating the absurdity of Murphy's Law for the first time in his life, he became hysterical. So did I. Listen closely... and hear me straining to sing "902" while doing my best tominimize lips quivering with suppressed convulsions.

"Ignition" may or may not satisfy your expectations, but if it proves anything it proves this; it takes a songwriter to be who he was before he can be who he is. That's not submitted in a spirit of artistic autonomy — I gave that up years ago, but the artist must do what he can to nullify the reality that floating on the edge of what he's created in the middle is endemic. With a wink and a smile, these songs throw the cement and dirty laundry in with the orange juice and cookies. "Ignition" ends with its tongue in its cheek. That's what the 60's was all about.

"Studio inventions by the creator of the Music Machine were never predictable. "Point of No Return," a powerful garage-punk slam to the brain was recorded in 1966, and combines all of the above as it reaches for the edge, finds it, and leaps into now. The original Music Machine always started cold, blasted into first, and tore a hole in the back wall of the garage after shifting into reverse. With a large endorsement from Vox, we unveiled our new amplifiers and proceeded to plunge into recording. Refusing by any measure of sanity to hear suggestions that we might be swimming in a sea of bewildered confidence, the band (myself included) twisted knobs and cranked sonic distortion that killed flying geese. The sound is still being investigated."

Sean Bonniwell

"King Mixer," a wry evaluation of a roady dealing drugs, provides a tongue-in-cheek look at the truth about it all when we pretended not to know what we pretend to know now. This song was recorded in don't ask-me-where New Mexico, on a four track machine using quarter inch tape: "Why are all these wires jammed into one plug? Hey, I've seen better headphones on a bombardier, come to think of it, this microphone looks exactly like the one Walter Pigeon used in Flight Command. Why is there a power failure every time I play a G chord? Where are we? In Reno? We can't see and we can't hear, but roll that tape anyway, I think it's time we got down to the sky."

Sean Bonniwell